With The French Connection, The Exorcist, Sorcerer, Cruising, To Live and Die in L.A., to cite only his most famous films, William Friedkin has made a deep impact on contemporary American cinema, establishing himself as one of the most talented and uncompromising of the New Hollywood filmmakers.

William Friedkin not only achieved recognition at the Oscars, and had two enormous hits in the 1970s (The French Connection and The Exorcist), he also invented a new approach to the cop, horror and action films, pitched between hyper-realism and hallucination; traumatised several generations of viewers and cinéphiles, and influenced a fair number of young directors. From The French Connection to Bug, William Friedkin has consistently explored his themes of choice: madness, hell, the narrow borders between reality and nightmare, Good and Evil. And often taken the risk of going too far and confusing the audience (e.g. the fiasco of his masterpiece Sorcerer and the polemic surrounding the production and release of Cruising).

Friedkin, famous for his masterly action scenes, has never claimed to be a genre director. He has directed several psychological dramas, such as the Harold Pinter adaptation The Birthday Party and The Boys in the Band, made at the start of his career. It is clear that his two most recent films Bug and Killer Joe display a kind of symmetry with his first films. Theatre + humour noir + sexual violence, is the winning recipe for Killer Joe, Friedkin’s new sucker punch of a film, and shows that far from quietening down with age, he relishes taking viewers on an emotional roller-coaster that is set in and around a caravan, and involves five insalubrious characters, all of them “dirty, ugly and bad”.

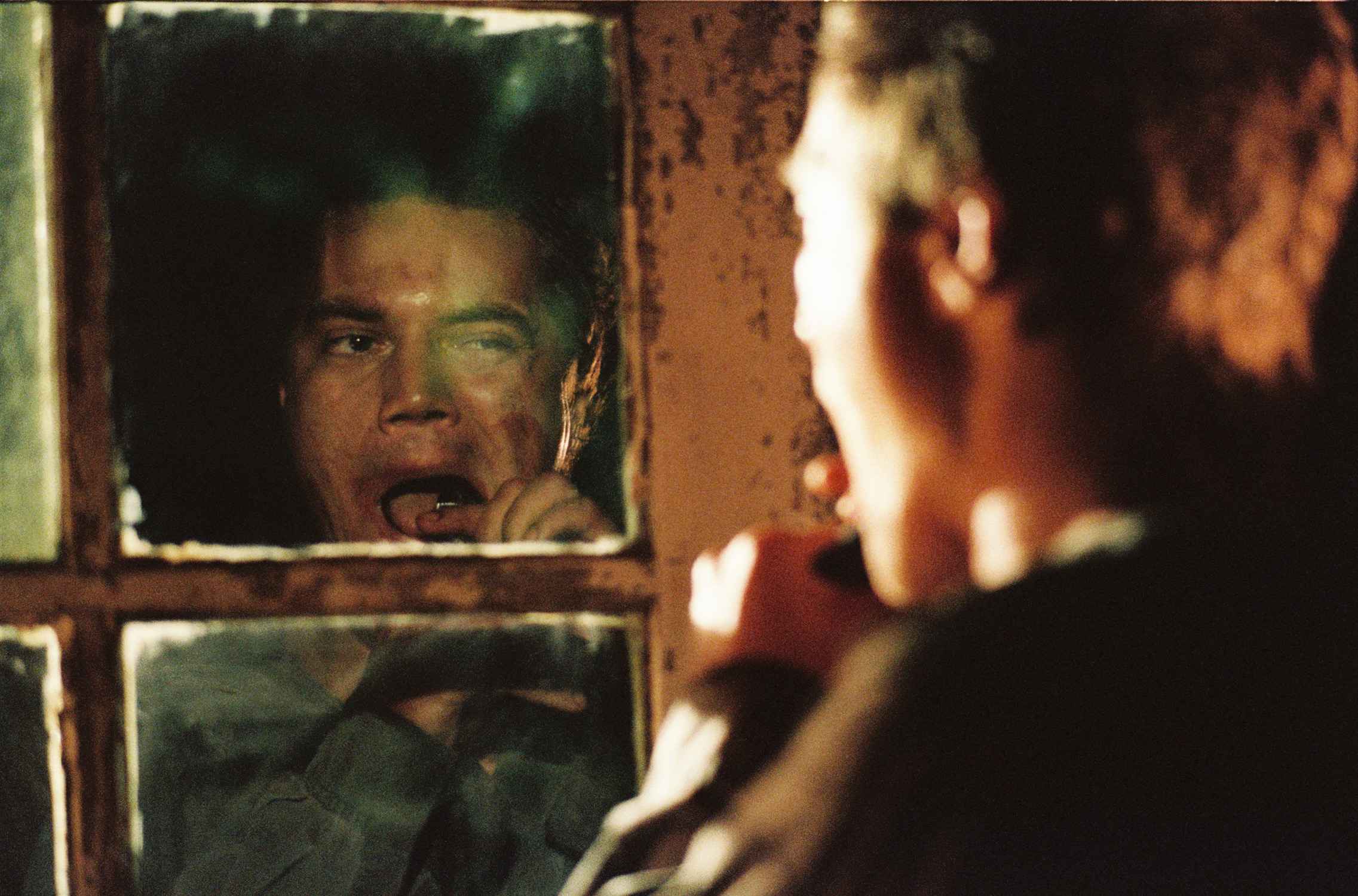

Six years after the formidable Bug, which revived cinéphiles’ interest in his work, Killer Joe confirms the filmmaker’s theatrical tendency, and in fact William Friedkin, in between directing numerous operas all over Europe, has staged a string of productions by playwright Tracy Letts. After the paranoid craziness of Bug, almost entirely concentrated within one motel room and featuring Michael Shannon and Ashley Judd, Killer Joe is a murderous family game that also unfolds for the most part in a seedy trailer-home. It is not the action scenes filmed on location that give the film its impact, but the extraordinary energy of the verbal confrontations between the various characters in the enclosed space of this familial conspiracy story that soon veers into violent and obscene family farce. As he comments in this interview, free of studio-imposed constraints, as well as audience expectations, (since the film was produced by Frenchman Nicolas Chartier, previously an instigator of Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker, and it will have a limited theatrical release in the USA), William Friedkin has doubtless found an opportunity in Tracy Letts’ stories to make his most personal films, that allows him free rein to his penchant for extremely black humour and extreme situations that reveal our basest impulses. William Friedkin, a survivor from the 1970s but still just as incisive a mind and talent, does not hide his disaffection with the present, and especially current film production. Friedkin makes a point of stressing his isolation and marginalisation within contemporary American cinema, to which he no longer has any desire to belong. His last two films are highly symptomatic of both a misanthropic turning, an increasingly paranoid and claustrophobic view of the world, but also of a filmmaker at the top of his form who delights in using his chamber films as explosive lessons in filmmaking thrown in Hollywood’s face. We met him in his favourite Italian restaurant in Beverly Hills.

It seems that your two last films Bug and Killer Joe emphasize the claustophobic dimension of your cinema.

“Most of the films I am most a fan of that I have made over the years deal with people in claustrophobic situations, like Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party, it is the favourite film of mine and it all takes place basically in one room. About one third of The Exorcist takes place in one room. The Tracy Letts films that I have done are really brilliantly written and they are about themes that I’m drawn to which are paranoia and obsession. And they played out in tight spaces, not in open country, the Wild West or even in the Streets. If you look at The French Connection, even how it is shot all over New York, it is basically a claustrophobic film, these guys are locked in their own world.

Bug and Killer Joe are based on two Tracy Letts’ plays.

Tracy Letts is the best playwright in America today, without a doubt. His last play won the Pulitzer Prize. People now recognize him. He wrote for himself. He felt no obligation to an audience, or to the actors or the director what it is about. And now people understand totally. They get it that it is on the oppression of the strong against the weak, the oppression of organized religion.

I feel the same. I am very happy if people like my films, or if they go to see them. If they don’t, it is not my problem. I never felt that about any of the films I made that were huge successes. It is not that I don’t care about the audience; it is that I don’t wish to depend on the audience. I know what the audience wants: superheroes, videogames, and stupid comedies. It may be that I would make a hit, but I couldn’t even watch it. I don’t want to make a film that I can’t watch.

What about American cinema today?

Clint Eastwood gave an interview the other day that I read and he talked about the difficulty he had getting Mystic River and Million Dollar Baby made. The studios didn’t want to make it, and it was done with outside financing and the studio distributor. He said he went to one studio head who he worked with – he didn’t name him but I imagine it is the guy at Warner Brothers who just left, Alan Horn, and he said to Eastwood: “we don’t make dramas anymore”.

I feel the studios are certainly in touch with a possible audience that is in America between 18 and 29, and they keep feeding that machine. Do you think Haneke is thinking about the audience when he is making Caché? I don’t think so and it is a great movie.

Most films that I admire should not been watched with your mind, but should be watched with your emotions. I think that a movie should at least attempt to move and audience.

Now the audience wants instant gratification. That is not an audience that I am seeking.

So I have to find a smaller audience, or not do films. I still love films but not the stuff that is for the most part being made here. I just think there are some very talented directors here, but not like they were when I wanted to make films, dozen of people all over the world whose films I could wait to see like Antonioni, Fellini, Kurosawa, Rossellini, the French New Wave… We waited every day for a new film.”

While we are talking with Friedkin, we are interrupted by two female diners, both aged around 50. They have been listening to our conversation and insist on giving us their opinion as to what they believe a good film to be: an entertainment that offers you a good time and makes you forget your everyday concerns, a film like The King’s Speech. They are interior designers. They have no idea of who they are talking to, and will never know. One of them is particularly vehement.

“Lady: When I go out of the theatre after a movie, I want to feel good, not to feel scared or misery

Friedkin: Did you ever see The Exorcist?

Lady: Yeah, scared the hell out of us

Friedkin: You don’t want that? You don’t want to be really frightened by a film?

Lady: That was great, clever, that makes you think.

Friedkin: What does it make you think?

Lady: Of the Devil

Friedkin: But you don’t need a movie to think of the Devil?”

They finally decide to leave us alone and leave. Friedkin, who has remained patient and polite throughout, rejoices:

“That will be marvellous in your interview. It makes my point. These perfectly normal American women probably have an education, are gainfully employed, what they are talking about I don’t have a clue. The movies they liked, “feel good movies”, are fucking awful, beyond stupid, like Sex in the City, Bridesmaids.

Do you think that it is possible to change the rules?

Killer Joe is very much against the grain. A handful of films that I can name changed the rules: The first one is Birth of a Nation. Not only to tell an epic story that was controversial and get a big audience but it changed the style in which films were made. The next film was Citizen Kane; it changed films completely in terms of the narrative possibilities. After that was Godard’s Breathless. When I made The French Connection I was conscious of Godard and the jump cuts.

What today? I don’t know. It is more than likely than a film like Killer Joe, an American made movie with a big movie star is too tough for an American audience.

I don’t want to make films for these stupid women, I don’t care what they like or don’t like. I don’t respect their opinion; that is not an audience that wants to be challenged; they just want to “feel good”. And what “feeling good” means is looking for stuff that is opium for the eyes, and nothing for the mind. Killer Joe is very much a challenge to an audience, and I know that. And I don’t expect a great audience for this picture, but it doesn’t matter to me. I would be happy if they were, but I am not going to change it.”

Despite the relative public and critical indifference to most of his films from the 1990s and first decade of the new century, the director’s prestige remains intact, as evidenced by the superb cast of Killer Joe, which contains some of the top talent in American cinema today, playing unflattering or particularly shocking roles: Joe, the corrupt cop with a sideline as a contract killer, is played by Matthew McConaughey, a million miles away from the pretty-boy leading roles in commercial productions we’ve got used to seeing him in recently, and he is accompanied by Emile Hirsch (Chris, the psychopathic, bad seed, son), Thomas Haden Church (Ansel, the somewhat simpleton father), Gina Gershon (Sharla, the rather slutty stepmother) and Juno Temple (daughter Dottie, somewhere between Lolita and Baby Doll). They have a field day with all the insanity and perversity, clearly egged on by the director. Gina Gershon, for whom this is a major comeback following her earlier stellar performances in Bound, Showgirls, The Insider and Demonlover, is brilliant and fully invests in her character; She is not the only one to appear naked in Killer Joe, a film that stands out as one of the most provocative American films of recent years, and relishes its abundance of risqué scenes.

Although Friedkin condemns the plethora of sex in some recent films, one could justifiably retort that his films have often been extremely graphic in their representation of sexuality, and particularly homosexuality, implicitly or explicitly, in several of his major films.

What do you think of the near-pornography of Killer Joe?

“A lot of people considered James Joyce’s “Ulysses” and Henry Miller’s “Tropic of Cancer” pornographic.

I don’t believe in heroes or villains, bad guys or good guys, and especially not for drama. So why should I put that in a movie? In The French Connection, the cop is worse as a human being than the French drugs smuggler. I don’t believe in the clichés of human behaviour.

In terms of cinema, like The Boys in the Band or Cruising, I believe that everyone has within him all of the male and female genes.

When I made those films there were people who actually thought that gay life was evil, and I saw The Boys in the Band as a love story, it happened to be a love story about men. Cruising simply uses the background of S&M as a kind of a strange police procedure. I believe that most of the people are sexually confused.

As a young man growing up in Chicago, I started out fucking whores, black prostitutes that I would pick up on the streets, because it was simply a matter of getting off. Now I find a great sadness in the whole idea that someone’s daughter has to become a prostitute. I could not have sex with a prostitute if she was the most beautiful woman on earth.

Once I achieved a little success I became attractive to women, and I fucked every woman I could. In the seventies, the directors had trailers on the set and they gave you blow jobs between shots. And I did this, everyone did, married men… I was single. It didn’t matter. Sexuality to me was not about love at all; it was to do with biology. The only love stories I made are Bug which is to me a strange love story, and about someone who is in love with another person captures their paranoia, and The Boys in the Band. But I am not drawn to show sex on the screen, in fact I find it mostly humorous. Have you watched two people having sex? We call it “the beast with two backs” It is ridiculous! I don’t enjoy putting sex on the screen; In Cruising, the sex is sex without love; in Killer Joe it is a kind of love story.”

Killer Joe is about the desperate need for family, not necessary sex, but family. Dottie is in a dysfunctional family, where her brother Chris and her father Ansel tried to pimp her out. And her mother tried to kill her, and her stepmother Sharla is nice to her but she is a slut. And Joe is a guy who only sees like most cops that I know the dark side of human nature.

Joe is interested in Dottie because if you listen carefully to what they said to each other early in the film, they both want the same thing, which is some kind of family. Tracy Letts’ work is about the search for family. In many ways that’s what The Godfather is about too: family.

Killer Joe is already famous for at least two highly unseemly scenes, of the kind that Friedkin is the only one today who still dares film, and throw in the face of puritan America. An opening scene that ends with full frontal female genitals on the screen, and a rape scene that involves a chicken wing, both a priori impossible in an American film but which are in the Tracy Letts play. Friedkin explains:

“I had written to Tracy and I said: “if I show the women in the opening scene the way you suggest it, we will probably have a X-rating. How would you feel if I show her only from behind?” He wrote me an eight pages memo saying: “don’t be afraid of the pussy. It is a signal to the audience to fasten their seatbelts; that this is going to be an unusual experience. Yes it is set in a trailer, but they are going to be things happening in that trailer that you do not expect to see.”

I understood that very well, why there was a need to show her that way. My initial impulse was that it could be distracting, but then he reinforced this idea that it is meant to be a comedy. The movie is a comedy, for the people that can get the jokes. But we have great response from women, so far, to my amazement!”

Interview conducted in Los Angeles on November 11, 2011, with Manlio Gomarasca, and published in Cinema Scope #49. Thank you to Mark Peranson.

Laisser un commentaire